Kaila Austin is an Indianapolis-based artist whose work largely aims to uplift and represent black arts and culture within communities through visual storytelling. Her art takes many forms, depending on what medium best depicts her subjects. Kaila uses her background in the arts and museum work to accurately capture reality through her own personal experience and lens. To see more of her art, check out Kaila’s Instagram!

You’re an artist of many mediums – a painter, muralist, bookbinder, and collage artist – what sparked your interest in those areas?

I started off using a sketchbook and drawing as a way to record my interactions with life. I went to school, to paint, so I started off at Ivy Tech in the fine arts program there. The first two years are foundational, so they give you a chance to try your hand at a lot of different mediums. I realized that such a flexible approach was something that was useful for me. Then I went to IU, where it was a very traditional painting program. It was realism and classicism and all that. I was bored with it because that has been done for hundreds of years. So, how do I make works that are entertaining for me to make and, therefore, entertaining to interact with? You can tell when someone’s bored making their work. That’s part of it, and another part comes down to who is sitting and how the medium interacts with who they are. So for some people, one medium isn’t enough to grasp their energy, and so that interaction and that playfulness of mediums becomes part of the piece where it shows up in the person.

How would you describe the art that you create?

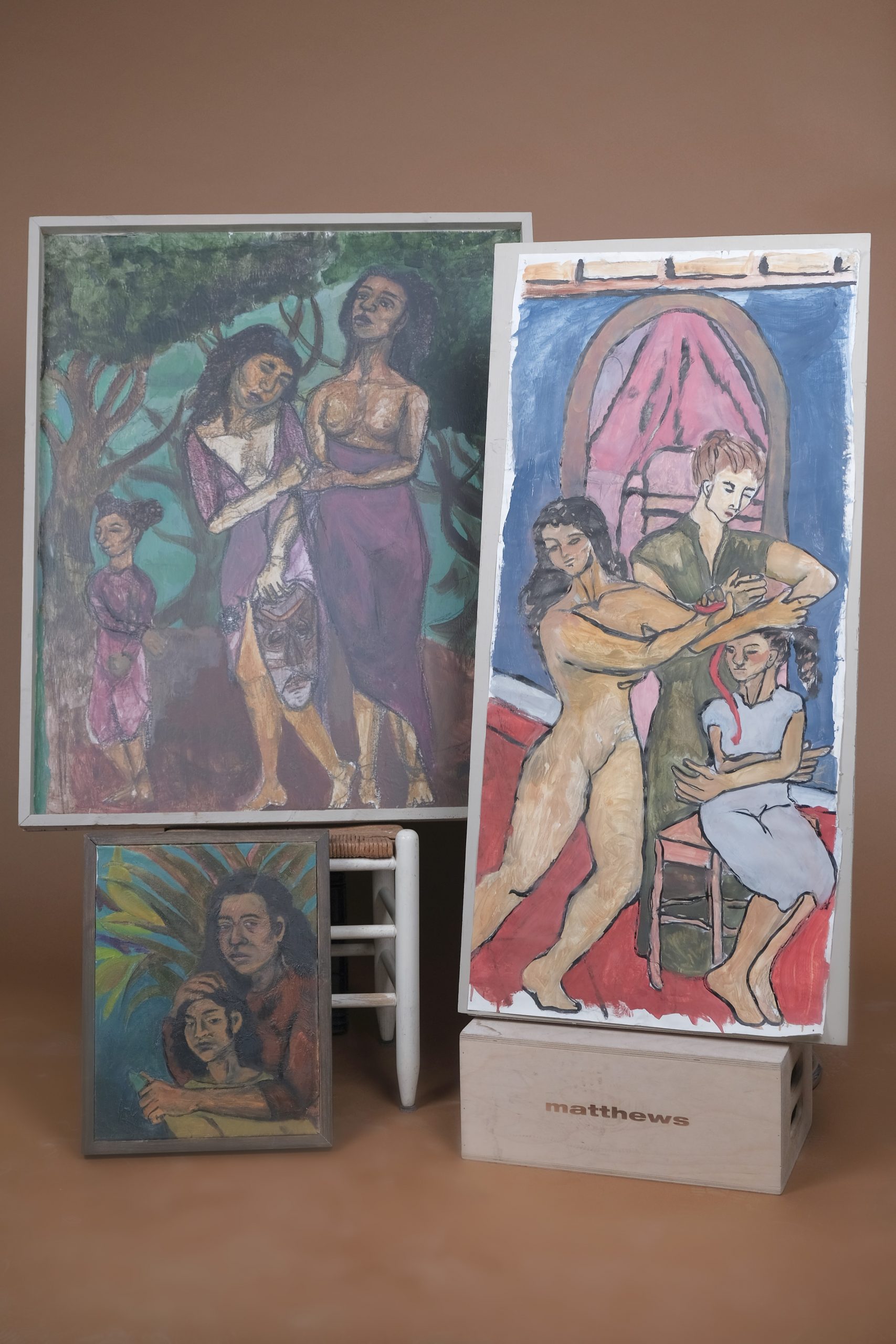

This is going to be so cliche! I like storytelling. I’ve had a medical condition for a long time that messes with the way that I perceive reality. The condition makes it so that I am always in a state of anaphylactic shock, so my body thinks that there’s something wrong when there isn’t. My sketch practice started off as a way to ground myself in reality. The condition makes me really dizzy, it even makes it hard to walk sometimes. Having the sketchbook as a grounding place for me was important. I have all of my sketchbooks since fourth or fifth grade, so you can go through and chronologically see how I was grasping reality at that moment. Partially, it’s personal narratives about mitigating the difference between an internal and an external self, or me as a mother, or me as a daughter, and how that all plays into my conception of reality. Recently, I realized I didn’t have the ability to visually tell the stories that I want to be able to tell with my work. I hadn’t practiced enough in my medium and painting figures in that classical way because I rebelled against it so hard in school. That’s what we all do in college, right? I was like “No, fuck traditional oil painting, I’m going to glue stickers onto this!” Over the pandemic, I took a step back and was like “Okay, there’s probably something to this whole classical painting style, or people wouldn’t do it for so long. There’s got to be something there that’s more than whatever I’m rebelling against.” I went back and have been working and doing more traditional figure studies and more of the stuff I consider boring work conditions to regain the skill set that I need to go back and do the storytelling that I like to do. The body of work that I brought with me shows a transition between wherever I was and wherever I’m trying to go.

Do you aim for your work to convey any specific message?

My work splits into two realms, so there’s this personal narrative that I’m trying to get back to, but a lot of my work focuses on how we can uplift our communities and work together. A lot of my pieces will be of local artists and musicians. The project that I’m working on right now with SEND – which is the Southeast Neighborhood Development Incorporation – is a storytelling project. I’ve been going around and sitting down with grassroots leadership in the community or elders that we call Memory Keepers and recording their stories and doing their portraits as I’m talking with them. That’s been a nice way to bridge that gap between how I afford to be a painter and the storytelling aspect, which is important. It helps that I have a black background in museums. I worked in exhibit planning and design for a decade. I’ve worked in archives, and as a curator, and in writing, so translating those skill sets back to my artwork, we can use the arts to preserve communities. We can use the arts to tell stories so we can use the arts to start to do restorative justice work, and what does that look like in Indianapolis?

When you are looking to create something, what inspires you?

I think a lot of it still leans back into the community. I’ll be out at concerts with my sketchbook drawing musicians as they’re working and then painting them later or getting to know people on an individual level, which influences my work. Also, the basic stuff – like flowers! I could take pictures and look at flowers forever and floral motifs show up a lot in my work because of it. My partner gets bothered with me when we travel because I was like, “We’re going to the botanical gardens, and we’re going to the farmer’s market, and that’s what’s going to happen!” Even with the farmers market, I think it’s that engagement and community that gives me the energy to keep doing this kind of work.

You had your first solo exhibition in March. How did you prepare for it?

That was saints and icons. I had a very specific goal for that one. When I was in my undergraduate program – IU has a “traditional” painting program – none of my professors there could teach me how to paint black skin. The question made them uncomfortable. That’s basic color theory, so it got to be frustrating. Like, “Well, you can do all this with anyone else, but when I ask you how to paint myself – ‘I don’t know,’ right?” I was working on this piece here, which is part of a larger triptych on motherhood, and I realized I can’t paint my own skin tone and I can’t paint anyone else’s skin tone outside of this European classical training mode. My goal for that exhibition simply was to learn how to paint people of color, specifically black people, in terms of how you mix color and trying to get a grasp on the medium. It’s super simple. I wanted to do that for now and we’ll see what comes next. I think it’s really important to represent everybody accurately. That was one of my goals. I didn’t want to neglect any group.

Did you feel that you grew as an artist from that exhibition?

Yeah, definitely! I have a bad habit of not pushing myself as much as I need to as a visual artist. For most of my career, I’ve been split between full-time museum work and reading and my free time. Even before the pandemic, I had left the museum because it’s an interesting institution to work underneath. I had to embrace being a full-time artist differently than I ever had before. That entire part of it was a learning experience, and I was really worried about the exhibition at the Harrison because all of my pieces feel so similar. When I was looking at them individually, I thought, “This is going to be monotonous. It’s going to be a boring, repetitive show.” I was upset about it, but once I installed everything, I was like, “Everything is so similar, but it’s all done so differently that it makes it so you’re approaching a different subject every time.” If I’m doing portraiture, that’s how I want it to feel. Each one is a different interaction with a real person, which is what mixed media allows me to do.

You have a lot of experience working in museums. Did being in that space influence your work as an artist?

Absolutely! My work in museums mostly centers around display, how we display the people and artifacts of different cultures, and what that does for how we engage with these cultures. Newfields was the subject of my thesis because it does this in an obvious way. There’s a concept called throughways. It’s an architecture term that determines how you will walk through a building, because architects plan the flow of spaces. We do the same thing in the museum where we direct where you’re going to go first, even if you’re not thinking about it. What do we do culturally when European galleries are the nicest ones – they’re going to be the first thing you see – and then the next floor is the Africa galleries, and that’s all cramped? The Africa and Asia galleries at Newfields are really dense – you feel crowded in. What does that do to the way that we perceive these cultures? Even as I actively attempt to push against those structures, I recognize I’m still using those same conventions, the same painting techniques, and the same subject matter that I’m pushing against, so how far can I push? That’s a debate that because of my place in the museum world, I’m always debating. The work I do is nice, but how much is it also nice because it’s fitting back into this narrative of what comes first? I don’t know, it’s an ongoing debate. The museum is an interesting institution and it culturally brainwashes people, even if we don’t realize that’s what it’s doing. Even the Van Gogh exhibit – it’s going to be completely life-changingly, experientially beautiful. But what comes with that? What do you learn from that? Especially being a mom, I’m always thinking about the places we take our children, and what you learn is important from those spaces.

You’ve painted some beautiful barricade murals around the city. How did you start doing those?

My first mural was through PATTERN for the Murals for Racial Justice with the Indy Arts Council. It was the four-panel piece with James Baldwin on one side and Audre Lorde on the other. I did that mural during Pride last year, so June 2020. I thought that was important to represent in that space in that moment, and it was heartfelt because black gay men were coming up to me while I was painting and being like, “Listen, I never thought I’d see myself represented in the city, so thank you for being out here and doing this.” After that, I went down to St. Louis and worked with an artist organization called Painted Black STL, and they were partnered with the Shakespeare Festival. They had a part of town that had all these abandoned storefronts because so many things closed throughout the pandemic. The Shakespeare Festival rented all the storefronts and hired 21 artists to come and do installations. It was a cool project because we did the Christmas Carol. I did the first scene where you were introduced to Scrooge. They were meant to be paintings and interactive sets, so on weekends actors would come and perform in these small boxes and travel to each of the 13 stops on the audio tour. That was my first out-of-state work mural work. It allowed me to play with both exhibit design and painting at the same time, which was a lot of fun.

I came back here and did the barricades at the City Market a week or two after. I had a residency at the City Market a few years ago with Big Car Collaborative where I did community portraits. I went through and found some of those, and then I went to the marketplace and actually sat there and drew people! I bought them coffee and drew them and had a goog time getting to know them. Those were the people that were on my barricades for that project. I thought that it was important to represent people who live here and exist in this space for that project.

What are your goals for the future as an artist?

This question shows up so often, I would think I would have a better answer by now! I don’t think that a year ago I could have even guessed that I’d be at this point in my career so quickly. I have to reorient myself a little bit. My five-year goals have happened in a year. I like working in the community and I like doing mural work, so if I can continue to figure out how to balance those two goals, that would be great. The art career is hard because I’m winging it. I’m taking it as it comes to me, which isn’t the best business model, but it’s working in terms of me giving things enough space to exist, which has worked so far. I don’t know – we’ll see where the journey takes us! I’d like to be so overwhelmed with opportunities that I can pass them on to other people, and it’s getting to that point already. If I can also use my work as a way to bring attention to and strengthen the arts community here, then that is an underlying goal, but in terms of the trajectory of my work – we’ll see!